Minds On

Warm up

Don't forget to do your safety check!

Warm Up

Breathe in and out

For our warm up activity, access this audio clip entitled "Breathing Activity" to learn more about taking deep breaths.

Breathing Activity

Find a comfortable position. Focus your attention on one part of the body at a time.

How does that part of your body feel? If possible, take a deep breath and allow your lungs to expand.

Now, focus your attention on one part of your body. Allow that part to relax before moving on to the next.

As you scan through your body, keep breathing deeply.

Once you have completed the scan, take a moment to stretch.

Drama game

Check out this video entitled “Environments” to play a game. In this video, the actors are imagining themselves in different environments. They pretend by using body movements, facial expressions, and vocal cues. Try following the actors and create your own actions.

You might try this game with a partner or small group and create your own environments. To end the game, either of you can use the words “end scene.”

Test It

Your turn!

Now, let's try it!

- Imagine being transported into a new environment.

- Explore the following carousel.

For each image, consider:

- What kinds of equipment and clothing would someone need?

- What kinds of activities would someone do in the environment?

- Would the weather suddenly change?

- Would there be animals in the environment? People?

- Act it out using gestures, movement, and/or facial expressions.

If possible, narrate the experience to a partner, or create a written or audio description.

Let's get started!

Brainstorm

Brainstorm

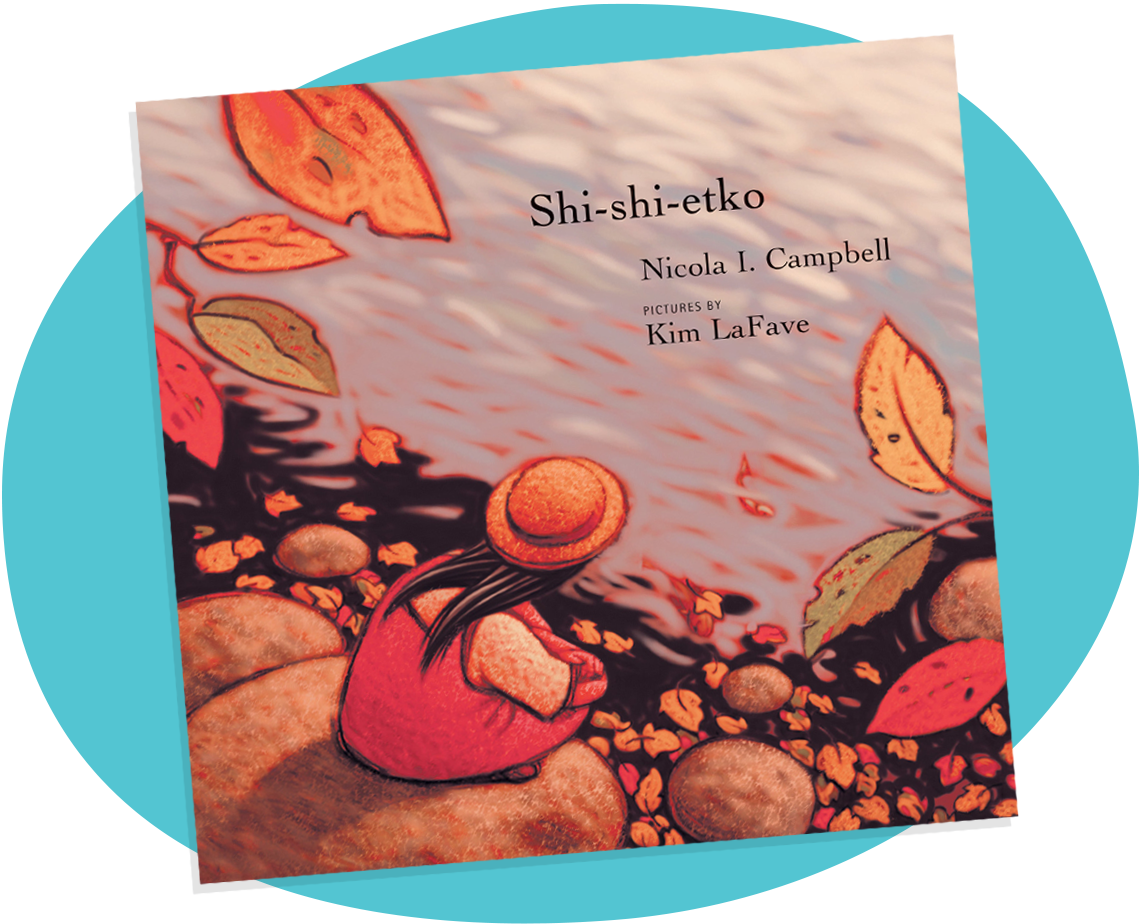

What do you notice about the following book cover?

Shi-shi-etko by Nicola I. Campbell, and illustrations by Kim LaFave

Consider:

- How does the artwork convey meaning?

- Based on the cover illustration, what do you think this story is about?

Record your ideas in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Action

Get ready, get set…

While the content in this learning activity is aligned to the curriculum, some content may be sensitive to individual learners. Consider reaching out to a trusted adult to share your feelings and questions.

Once we have finished exploring, we might take our reflections and thoughts about a story and present through a monologue. A monologue is a long speech by one character in a drama, intended to share that character's thoughts and feelings with the audience. In this case, you will use the monologue to express your own thoughts.

Shi-shi-etko

In the Minds On, you examined the cover page of the story Shi-shi-etko by Nłeʔkepmx, Syilx, and Métis author, Nicola I. Campbell.

As you explore the story, consider the important parts of the story and how these might be emphasized if it was presented as a play or performance.

Consider how you might connect to the characters and relationships in the story.

At the end of the story, you will be creating your own response to the story and then turning that into a personal response monologue.

Did You Know?

Did you know?

Nicola I. Campbell is named after the Nicola Valley in British Columbia, which is on the traditional territories of the Nłeʔkepmx and Syilx nations.

Nicola I. Campbell

Nicola Lake and Valley, British Columbia

Before presenting the text, Nicola I. Campbell wrote a preface to help the audience to understand the context around the story of Shi-shi-etko and their family.

Press ‘Let's check!’ to access a definition.

Preface is an introduction to a text, which helps the reader understand the subject, theme, and/or goal of the text.

Reading Time

Preface

Let's explore the preface for the book, Shi-shi-etko.

“This story is about a little native girl names Shi-shi-etko, which means “she loves to play in the water.” Shi-Shi-etko's people have always lived in North America, hunting, fishing, and gathering traditional foods and medicines, making their own clothing and building their own houses, making their own rules and taking care of their traditional territories, telling stories, singing, and dancing. Native children were loved so much that the whole community raised them together – parents, grandparents, aunties, uncles, cousins, and elders.

But now Shi-shi-etko has to go to Indian Residential School. It is the law. The school is far away from her home, and she will have to travel for a couple of days to get there. Once she arrives at the school, she won't see her parents for many months or even years, she will lose her traditional name, and she will be forced to speak English – a language she doesn't know.

For a long time, the Canadian government believed that native people were uncivilized and made laws forcing native children as young as four, although generally between the ages of five and six, to go to residential school to learn European culture and religion. Parents were put in jail if they didn't send their children to these schools. Can you imagine a community without children? Can you imagine children without parents?

Residential schools had a huge impact on native people around the world, not only in Canada, but in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, as well. They resulted in a devastating loss of native traditions, languages, and cultures. The last residential school in Canada closed in 1996.

The effects of the residential school system continue to hurt native people today. It is said that it will take seven generations for our people to heal.”

Residential schools

Reflect on the following questions:

- What do you know about the history of the Indigenous peoples in Canada?

- Did you know about the residential school system before exploring the preface?

- If so, what can you recall about what you have learned?

Record your ideas in a notebook or another method of your choice.

In the preface, the term “Indian residential school system” is used.

The word “Indian” in this context is used to reference a historical event and era. The term was commonly used in the past to describe First Nations peoples, but today we understand and recognize that this word does not accurately reflect these distinct nations and their unique cultures, knowledges, traditions, and histories.

This word is considered an unkind and an inappropriate word, also known as a slur.

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples respectively attended residential schools during this era. There were 139 identified residential schools that operated in Canada from 1831 until the last school closed in 1996.

The residential school system is a painful part of Canadian history. It is important to understand the unique history of all people, so that we can understand, connect, respect, and stand up to help each other.

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples respectively have been mistreated and oppressed in the past, but this treatment also continues in various aspects of Indigenous life today.

By learning about the past, we can make connections to the present, and work towards a better future for everyone.

Reading Time

Residential school era

Let's explore the following text, “Learning about the Residential School Era,” written by Jerica Fraser.

|

During the residential school era, the government and churches did not recognize the positive elements of Indigenous family and community life. Rather, they viewed Indigenous peoples as different from, and in turn less than, Europeans and their culture and religion. They believed that this “difference” needed to be fixed and that Indigenous people needed to be more like European society. This process is referred to as assimilation and is not only harmful but is also violent in nature. Generations of Indigenous children were taken from their homes and communities to attend schools that were sometimes hundreds of kilometres from where they lived. It became illegal for Indigenous parents to keep their children at home if they were school age. Some students were taken at even earlier ages and some did not return to their communities until the age of 18, if at all. As a result, many lost connections to their home communities and did not grow up learning from their parents, grandparents, or community Elders or Knowledge Keepers. Instead, they were raised by nuns and priests and were purposely removed from their rich and vibrant communities and lives. In addition, generations of Canadians also were only taught about the negative parts of Indigenous life and community which perpetuated incorrect and harmful stereotypes about Indigenous peoples. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples have many beautiful stories that include laughter, love, resilience, resistance, and joy. Indigenous peoples today live in many different communities in and outside of their homelands and many continue to practice their languages, cultures, and traditions despite the attempts made by the government and churches against them. It is important to learn about these stories alongside Indigenous experiences of oppression, racism, and trauma within Canada. As Justice Murray Sinclair, former Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission stated, “education got us into this mess, and education will get us out of this mess.” Source: http://nccie.ca/reconciliation-and-nccie/ |

Press the ‘Activity’ button to access Learning about the Residential School Era.

After exploring the text, respond to the following questions:

- What happened during the residential school era?

- What was the reason why the government and churches developed the residential school system?

- What beliefs do you think the government and churches held that prevented them from being able to understand the reality of what Indigenous families and communities were like?

- Based on what you have learned, what do you think might have an impact on Indigenous children and their families and communities from residential schools?

Record your ideas in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Guided reading

Shi-shi-etko is a story that shares the voices of an Indigenous family before Shi-shi-etko goes to residential school.

As you explore the story and each page, think about the kinds of values, teachings, knowledge, and traditions that are taught within Shi-shi-etko's family and community.

Do you have any questions before beginning to explore the story?

Record your questions in a notebook or another method of your choice. If possible, share your questions with a partner.

Time with mother

Explore the following pages:

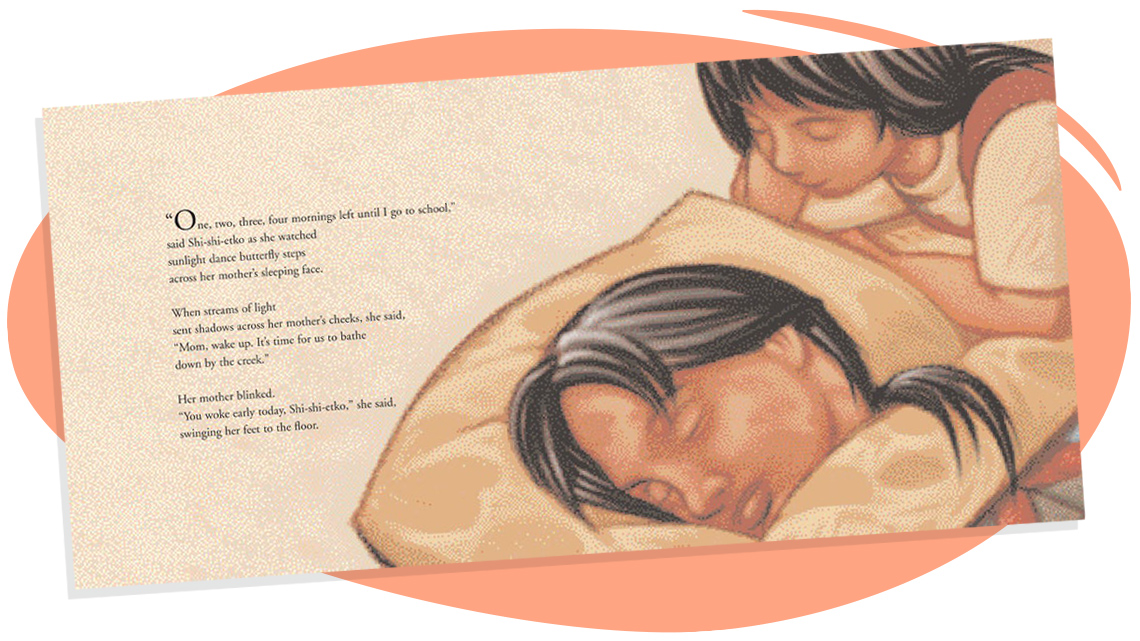

Page 1 & 2

“One, two, three, four mornings left until I go to school,” said Shi-shi-etko as she watched sunlight dance butterfly steps across her mother's sleeping face.

When streams of light sent shadows across her mother's cheeks, she said, “Mom, wake up. It's time for us to bathe down by the creek.”

Her mother blinked. “You woke early today, Shi-shi-etko,” she said, swinging her feet to the floor.

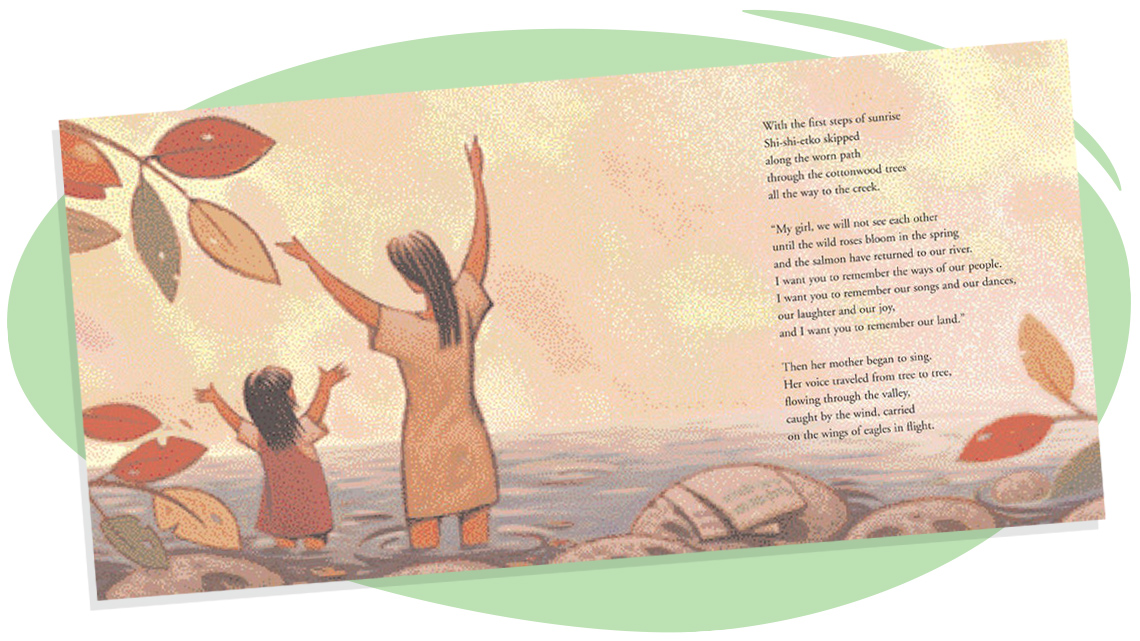

Page 3 & 4

With the first steps of sunrise Shi-shi-etko skipped along the worn path through the cottonwood trees all the way to the creek.

“My girl, we will not see each other until the wild roses bloom in the spring and the salmon have returned to our river. I want you to remember the ways of our people. I want you to remember our songs and our dances, our laughter and our joy, and I want you to remember our land.”

Then her mother began to sing. Her voice traveled from tree to tree, flowing through the valley, caught by the wind, carried on the wings of eagles in flight.

After exploring the previous pages from Shi-shi-etko, reflect on the following questions:

- Why do you think “I want you to remember” is repeated? What effect might this have on the audience in a staged/theatre version of the story?

- What aspects in life and nature reflect the number four? (Hint: seasons)

- Why might the number four be significant to Indigenous peoples and referenced in this story?

Record your ideas in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Press 'Let's Check!' to access a possible response.

I think the number four is represented by the seasons and the four directions (North, East, West, and South).

The number four is often associated with different Indigenous teachings across Turtle Island. Most commonly it reflects the Medicine Wheel and the teachings of the four directions that also contains teachings on how to balance the self.

Four is reflected in the medicines, the stages of life, the aspects of life (e.g., mental, spiritual, emotional, and physical), the seasons, the elements of nature (water, earth, fire, and air) and much more.

I think it is included in the story because it shows how Indigenous peoples are connected to and listen to nature. This book shares their perspectives before they are forced to learn another way.

Reflections and family

Explore the following pages:

Page 5 & 6

Shi-shi-etko could not help herself. She looked at everything—tall grass swaying to the rhythm of the breeze, determined mosquitoes, working bumblebees. She memorized each shiny rock, the sand beneath her feet, crayfish and minnows and tadpoles that squirmed between her toes, all at the bottom of the creek.

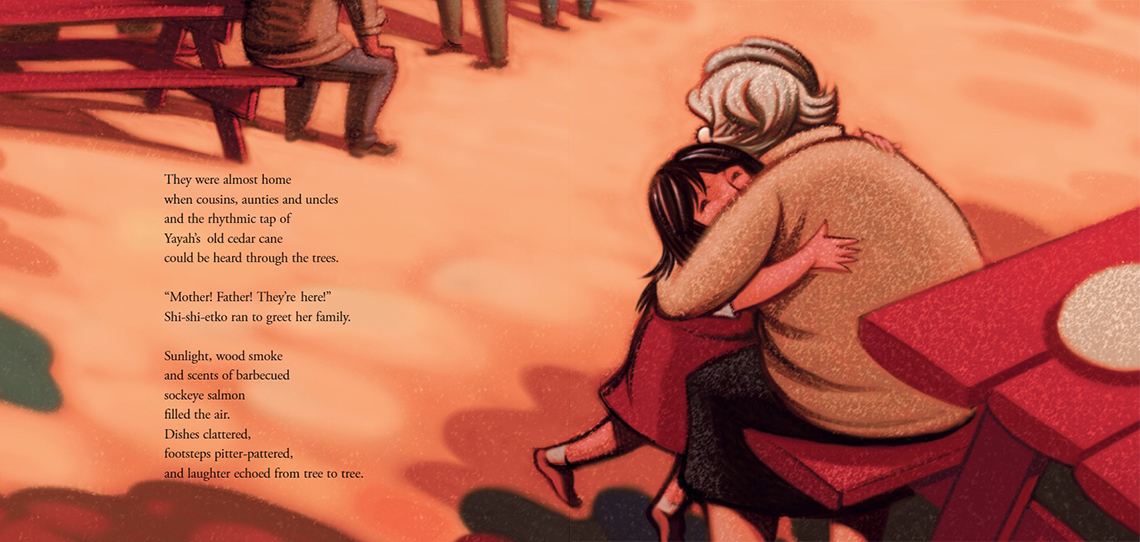

Page 7 & 8

They were almost home when cousins, aunties and uncles and the rhythmic tap of Yayah's old cedar cane could be heard through the trees.

“Mother! Father! They're here!” Shi-shi-etko ran to greet her family.

Sunlight, wood smoke and scents of barbecued sockeye salmon filled the air. Dishes clattered, footsteps pitter-pattered, and laughter echoed from tree to tree.

After exploring the recent pages from Shi-shi-etko, reflect on the following questions:

- What words come to mind that describe the gathering of Shi-shi-etko's family?

Brainstorm a list of words and record your thoughts in a notebook or another method of your choice. Share these words with a partner, if possible.

Day 3 and time with father

Explore the following pages:

Page 9 & 10

Afterwards in the late-night silence, tucked safely under Yayah's patchwork quilt, Shi-shi-etko counted her fingers. “There are only one, two, three more sleeps until I go to school.”

In the morning, when Shi-shi-etko woke, the sky was changing, navy to brilliant blue. She lay listening to the cool autumn breeze sing morning songs.

Soft…drum…heart…brass.

After exploring the previous page, respond to the following questions:

- How does the author share the passage of time?

- What do you notice about the illustrations from one page to the next?

- How might we show the passage of time in a staged drama performance?

Record your ideas in a notebook or another method of your choice.

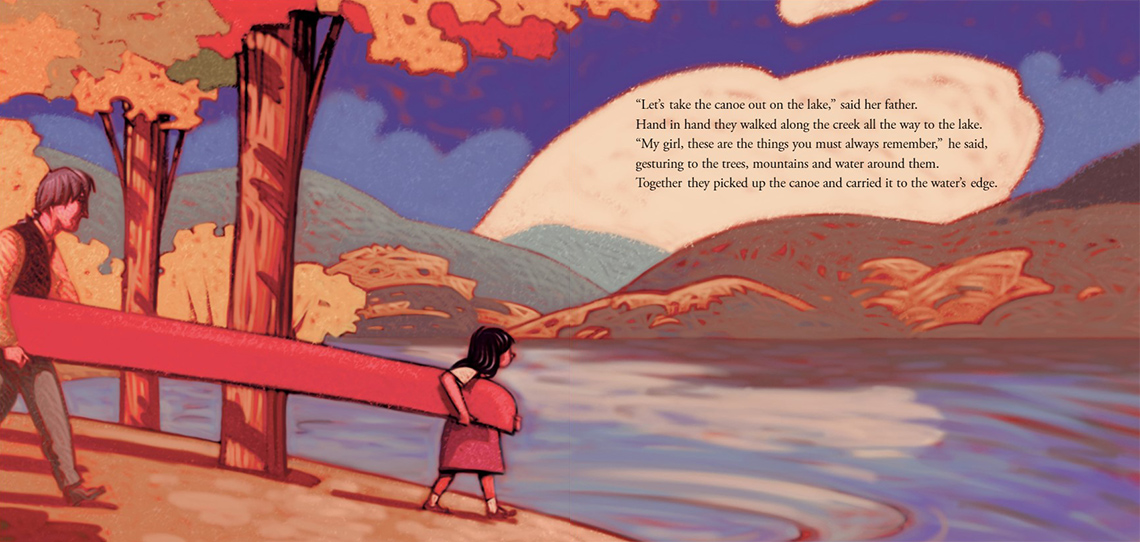

Page 11 & 12

“Let's take the canoe out on the lake,” said her father. Hand in hand they walked along the creek all the way to the lake.

“My girl, these are the things you must always remember,” he said, gesturing to the trees, mountains and water around them.

Together they picked up the canoe and carried it to the water's edge.

Page 13 & 14

With yellow cedar puddles, they strolled across smooth water.

Reach, dip, pull back…

Reach, dip, pull back…

The only sounds they heard were the whistling birds and their paddles breaking the surface of the lake, surrounding the with ripples.

Circle on…circle on…circle…

Her father sand the paddle song that her grandfather used to sing. His voice traveled across the water, a chant that kept their pace.

After exploring the previous pages from Shi-shi-etko, reflect on the following questions:

- What is similar about Shi-shi-etko's mother's and father's advice to her?

- What do you think this means about the realities of residential school?

Record your thoughts in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Reflections and bedtime

Explore the following pages:

Page 15 & 16

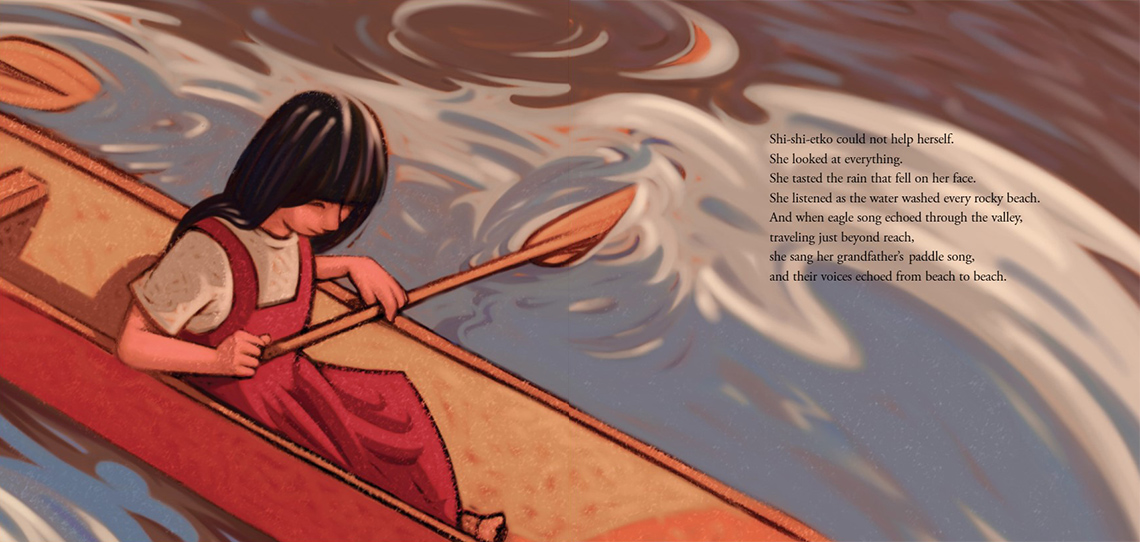

Shi-shi-etko could not help herself. She looked at everything. She tasted the rain that fell on her face. She listened as the water washed every rocky beach. And when eagle song echoed through the valley, traveling just beyond reach, she sang her grandfather's paddle song, and their voices echoed from beach to beach.

Page 17 & 18

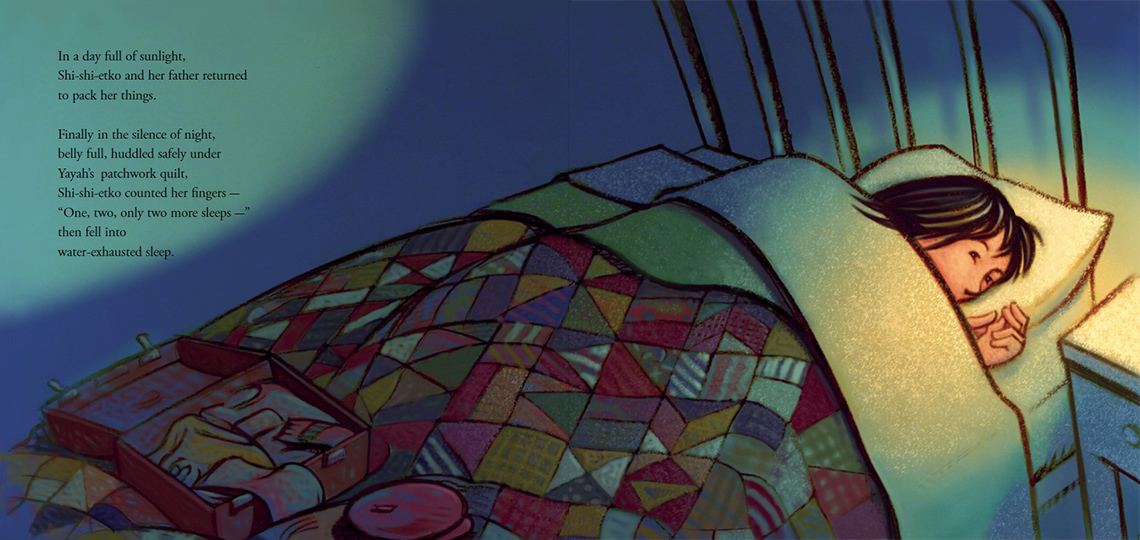

In a day full of sunlight, Shi-shi-etko and her father returned to pack her things.

Finally in the silence of night, belly full, huddled safely under Yayah's patchwork quilt, Shi-shi-etko counted her fingers— “One, two, only two more sleeps—” then fell into water exhausted sleep.

After spending the day with her father, Shi-shi-etko takes some time to reflect by herself at the water and in her bed.

Are these reflections similar or different than what Shi-shi-etko shared after spending the day with her mother?

Share your thoughts with a partner, if possible.

Yayah and memories

Explore the following pages:

Page 19 & 20

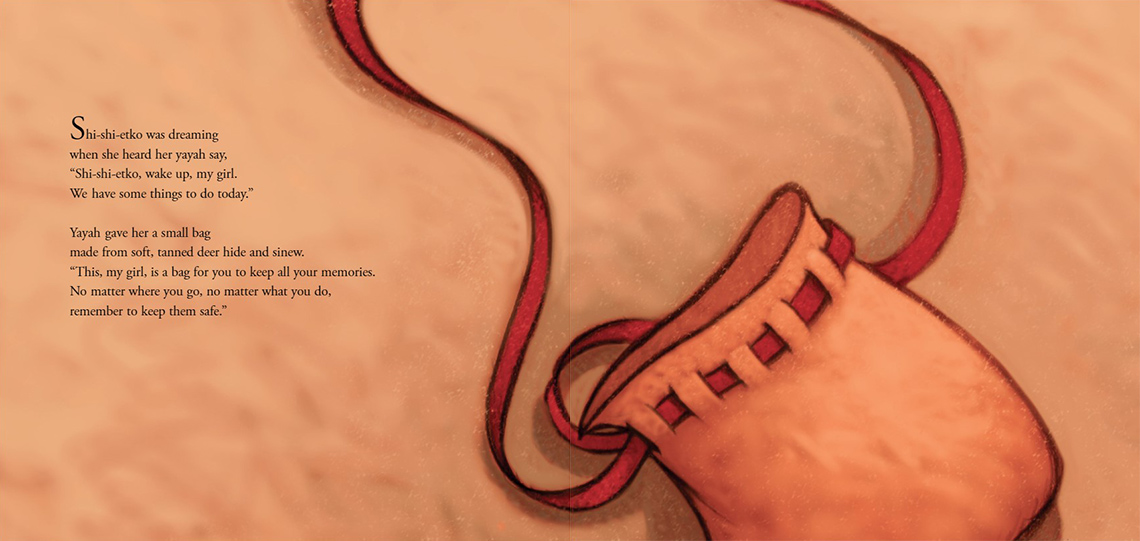

Shi-shi-etko was dreaming when she hear her Yayah say, “Shi-shi-etko, wake up, my girl. We have some things to do today.”

Yayah gave her a small bag made from soft, tanned deer hide and sinew.

“This, my girl, is a bag for you to keep all your memories. No matter where you go, no matter what you do, remember to keep them safe.”

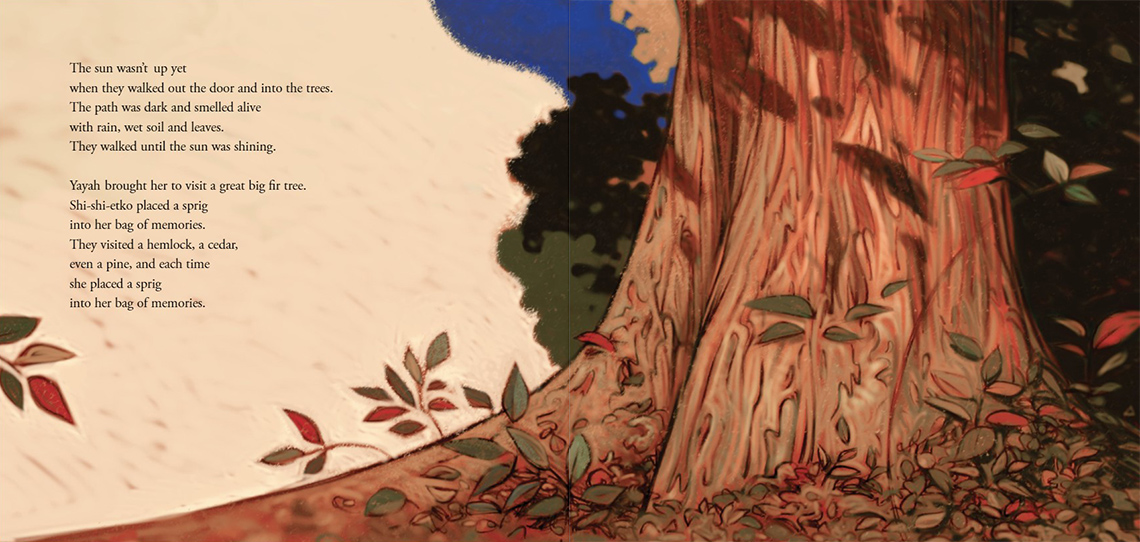

Page 21 & 22

The sun wasn't up yet when they walked out the door and into the trees. The path was dark and smelled alive with rain, wet soil and leaves. They walked until the stun was shining.

Yayah brought her to visit a great big fir tree. Shi-shi-etko placed a sprig into her bag of memories. They visited a hemlock, a cedar, even a pine, and each time she placed a sprig into her bag of memories.

After exploring the previous page, respond to the following questions:

- What is Shi-shi-etko's memory bag made of?

- What knowledge might you need to create a bag made from these materials? Do you think it would be easy or difficult?

Record your ideas in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Press 'Let's Check!' to access possible response.

A medicine pouch or moccasins are traditionally made from tanned deer or moose hide.

Did You Know?

Did you know?

Carving is an art form in many different First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and Indigenous communities across Turtle Island.

For some, it is a traditional art form, and for other communities it is more of a contemporary way to share traditions and lived experiences.

In the territory where Shi-shi-etko is from, there is a long history of using art and carving to tell stories in the form of pictographs and petroglyphs.

Many artists acknowledge and incorporate this history in their artwork today.

For example, Syilx artist, Clint George, continues the carving tradition and uses their art to teach people today about Syilx creation stories, histories, and traditions.

Learning with Yayah

Explore the following pages:

Page 23 & 24

They went to visit silver willow, red willow, sage brush, cottonwood, Labrador bushes and even kinnikinnick. They visited blueberry, salmonberry, saskatoon and huckleberry bushes. They found bitterroot, wild potato and wild celery patches. On and on they wen through fields of wild roses, Indian paintbrush, fireweed and columbine.

Page 25 & 26

Shi-shi-etko promised herself, “I will remember everything.”

Each plant they came to, she listened carefully to its name.

Then asked once, twice, even three times, “Is it food or medicine, Yayah? Is it always safe?”

Then, whispering its name, she placed dried berry, root, flower and fragrant leaf into her bag of memories.

That night when Shi-shi-etko crawled under her patchwork quilt, she counted her fingers and said, “One, only one more sleep.”

After exploring the recent pages from Shi-shi-etko, reflect on the following questions:

- “Is it food or medicine Yayah?” What do you think Shi-shi-etko means by this?

- Why are these items selected for the memory bag important to Shi-shi-etko? What do you think they represent?

Record your ideas in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Did You Know?

Did you know?

Indigenous peoples have been living on the lands, in what is now known as Canada, since time immemorial, or as long as can be remembered.

With each generation, they have learned from their environment about how best to take care of it, and how the land can also take care of the people if treated right. This is called traditional ecological knowledge.

This knowledge comes from the observations of generations of Indigenous peoples living on the land, each learning about specific plants and medicines that exist in the local environment to help provide for and heal the people in the community.

For instance, braided sweetgrass is a sacred plant for religious ceremonies. Some plants are sacred and are considered medicine. They have deep meaning to the community, so they are only used in specific ways and purposes. Even as time goes on, this knowledge adapts to the ever-changing environment. Each nation has its own beliefs, laws, and teachings regarding how to care for and sustain the Earth.

Planting the memory bag

Explore the following pages:

Page 27 & 28

At home the cattle truck that gathered children waited. Shi-shi-etko picked up her bag of memories, a pinch of tobacco for offering, then went out the back door to her favourite place beneath a great big fir tree. She placed the tobacco at its base, then tucked her bag inside its roots.

Dear Grandfather Tree,

Please keep my memories and my family safe. I will be home in the spring.

“Shi-shi-etko, come inside now. It's time for you to go.”

When they rattled down the dirt road and into the trees, Shi-shi-etko held a sprig of fir close to her heart.

Page 29

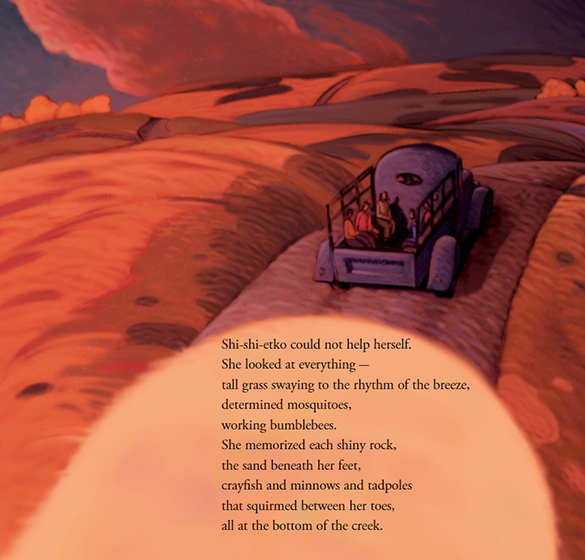

Shi-shi-etko and the other children are seated in the back of a low, dark purple cattle truck. The truck is heading on dark coloured road that is winding over many hills. The sky is dark blue, and the sun is setting in the evening, with warm orange tinges over the land and hills. However, over the truck, there is the shadow of a cloud resulting in a brownish orange over the children and the truck.

Text: Shi-shi-etko could not help herself. She looked at everything— tall grass swaying to the rhythm of the breeze, determined mosquitoes, working bumblebees.

She memorized each shy rock, the sand beneath her feet, crayfish and minnows and tadpoles that squirmed between her toes, all at the bottom of the creek.

After exploring the previous page, respond to the following questions:

- What do you notice about the cattle truck and/or the colours used to illustrate this page?

- Why is “remembering” so important to each person in the family?

Record your ideas in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Go!

Choose either of the following options to reflect on for a personal response.

Press the following tabs to access personal response options.

Consider the following questions:

- What did you learn from the characters in the text?

- What can we learn about Indigenous families and relationships from the story?

- Did you connect with the text? If so, how?

For example, your connection to the story might have been an emotional, spiritual, physical, or mental connection.

Record your personal response in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Consider the following questions:

- If you did not read the preface and know about residential schools, how might this story be read differently?

- Why is it important to know this history before reading the story?

- How does language and imagery in the story help illustrate the importance of land to Indigenous peoples? What words were used?

Record your personal response in a notebook or another method of your choice.

Consolidation

Monologue

Before you create your personal response monologue, let’s explore an example. Explore this video entitled “Monologue” to learn more about how actors use monologue to communicate their ideas and emotions to the audience.

Portfolio

Personal response

Using your response to either option in the Action section, you will be creating a personal response monologue.

In addition, an actor considers their audience as they prepare a monologue. Refer to the following questions to guide you.

- Who is my audience?

- What do I want to say to the audience?

- Are my thoughts and ideas clear?

Practise your monologue and when you feel ready, present your monologue to a partner, if possible. You may also create an audio or video recording.

Consider adding your work to your drama portfolio.

Reflection

As you read through these descriptions, which sentence best describes how you are feeling about your understanding of this learning activity? Press the button that is beside this sentence.

I feel…

Now, record your ideas using a voice recorder, speech-to-text, or writing tool.

Discover MoreExtend you learning about residential schools by researching more about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and its Calls to Action.

If possible, share your thoughts and learning with a partner.