Minds On

What is sovereignty?

Brainstorm

Brainstorm

A simple way to understand sovereignty is to think about a nation like a family.

Think about a family you know from television or in a book you’ve read or listened to. Next, think about all the roles and responsibilities in that family.

- Who makes the rules?

- How does the family make decisions?

- What roles does each member play in making the family work together?

Record your ideas using a method of your choice. Make sure you’ve recorded all members of the family and what each is responsible for.

Review your ideas. Does anyone outside the family have a say in how the decisions are made?

You might notice that this family makes decisions for themselves without outside influence. This is an important part of understanding sovereignty.

Sovereignty is the right of a country or nation to self-govern, to exert its authority within a territory. A sovereign nation is independent and able to govern itself without interference from other nations. Canada, for example, is a sovereign nation.

With this definition in mind, record a few characteristics of what makes Canada a sovereign or independent nation. Add your ideas to your list from before.

You may have listed that Canada is an independent nation that is no longer controlled by Britain. It has its own government structure, which controls and exerts authority over its own territory. Canada also has its own constitution.

Action

Indigenous sovereignty

Before the European colonizers arrived in what is now referred to as Canada, Indigenous peoples were independent nations. Indigenous communities were very diverse. Each nation, community, and territory had their own ways of ensuring the land and the people were cared for based on their specific governance structures.

Indigenous nations were also independent from control of foreign nations. When the French, and later the British, began monopolizing the territory that would later become Canada, Indigenous nations and their sovereignty were increasingly challenged.

In this learning activity, you will learn about different ways in which Indigenous sovereignty was infringed upon through different legislations and policies between 1890 and 1914. However, you will also learn about how Indigenous peoples resisted, lobbied, and fought for their rights in the past and continue to resist in present-day.

Key terms

Before you get started, it is helpful to review some terms and definitions that will be used throughout this activity and help you learn about the distinctions between First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.

It is important to note that the word “Indian” will be used throughout this learning activity, because it is deeply entrenched in law and policy in this country.

Over time, several terms have been used to refer to Indigenous peoples. The original term, "Indian," was replaced by the term "Aboriginal." Today, we use the term "Indigenous."

Press the tabs to learn more about the progression of terms.

Check your understanding!

For each description, select the corresponding term.

Definitions

As you work through the various tasks in this learning activity, it is important to note the following definitions:

Assimilation

It is the process whereby individuals or groups of differing ethnic heritage are absorbed into the dominant culture of a society (also, assimilate).

Colonialism

It is the policy of establishing political control by one nation over another nation or region, sending settlers to claim the land from the original inhabitants and taking its resources. It is a philosophy of domination, which involves the subjugation of one or more groups of people to another (See also colonization).

Press each term to access its definition.

The process in which a foreign power invades and dominates a territory or land base inhabited by Indigenous peoples by establishing a colony and imposing its own social, cultural, religious, economic, and political systems and values. A colonized region is called a colony.

The unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people or things, especially on the grounds of age, race, sex, or culture.

Destroy or completely put an end to.

Among Northwest Coast First Nations, a gift-giving ceremony and feast held to celebrate important events and to acknowledge a family’s status in the community.

A group of people involved with each other through persistent relations, or a large social grouping sharing the same geographical or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations.

The right of a country or nation to self-govern, to exert its authority within a territory

A formal agreement between two or more parties. In Canada, treaties are often formal historical agreements between the Crown and Aboriginal peoples; these treaties are often interpreted differently by federal, provincial, and Indigenous governments.

Task 1: Legislation, treaties, and land grants

Read the following passages on The Indian Act, the Numbered Treaties, and the land grants to the Moravian Church. As you read the passages, complete jot notes about significant peoples, places, and events that you notice. Record your findings in a method of your choice.

Use the following historical significance checklist to assess the historical significance of each event and its impact on Indigenous sovereignty.

Historical significance checklist

Record your findings in a method of your choice.

The Indian Act

The Indian Act is federal legislation passed in 1876 that regulates First Nations identity, rights, terminology, and governance in Canadian communities. The Indian Act sets out certain federal government powers and responsibilities regarding First Nations and reserve land. It does not include Inuit or Métis peoples, though the Indian Act at one point was amended to include the Inuit in 1924. The Act was created by Parliament without any consultation from First Nations communities.

Before the Indian Act was enacted in 1876, it was preceded by other legislation (later combined to form the Indian Act), such as the Act to Encourage the Gradual Civilization of Indian Tribes in this Province, and to Amend the Laws Relating to Indians (also known as the Gradual Civilization Act) in 1857, and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act in 1869.

Enfranchisement meant that a First Nations person would relinquish their status and become a Canadian citizen. The purpose of the Act was clearly stated in its full title, as it reveals the government’s plan to have First Nations peoples rescind their status and become “civilized,” as defined by the government, and part of the Canadian population. It promised that an “Indian” would receive land and be able to vote in exchange for their Indian status.

The main priority for such legislation was assimilation.

Press ‘What Does This Mean’ to access the implications of all these legislations.

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald said in 1887:

"The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change."

One of the ways the federal government sought to assimilate First Nations communities was through dissolving their governance structures. The Act created a reserve system to manage First Nations territories. A reserve is a tract of land which Her Majesty or the Crown holds title to. It meant that First Nations peoples no longer technically owned the land and could only use the topsoil of the land without any right to sell or claim ownership of it according to the Canadian government. The reserve was meant to control the movement of First Nations peoples and meant the Canadian government would oversee the lands, resources, education, membership, finances, and governance.

The Indian Act also legislated each community to have a band council, which is an elected system that would replace traditional structures such as hereditary and clan systems. Band councils are led by an elected chief and councilors and are responsible for the governance and administration of the community.

This Act was enforced through the Department of Indian Affairs (now Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada). Over time, the Indian Act has gone through several amendments. Many of the initial amendments forbade First Nations and their communities from expressing their cultural identities, specifically forbidding cultural ceremonies such as potlatch. The amendments also required children to be sent to residential schools to be educated. Although the Indian Act has been amended in many ways, it is still legislation today.

Explore the following video about the Indian Act. As you are exploring, record your thoughts using a method of your choice. How does the Indian Act limit the rights and freedoms of First Nations peoples?

Press ‘Possible Notes From the Video’ to access thoughts that you might have had while exploring the video.

As you were exploring the video, you may have recorded the following jot notes:

- The Indian Act denied women rights because women would lose their Indigenous status if they married a non-Indigenous person. However, if a man married a non-Indigenous woman, then it would make that woman Indigenous under the law.

- The Indian Act created reserves that were used to hold Indigenous peoples until they fully assimilated to European colonizer ideals.

- The Indian Act renamed Indigenous peoples with European names.

- The Indian Act restricted Indigenous peoples from leaving reserves without the permission of settlers.

Check your understanding

For each sentence, fill in the blank with the correct word or phrase.

The Numbered Treaties, 1871-1921

Eleven treaties cover an enormous area of land in what is now referred to as Canada. Explore the following Heritage Minutes video about the treaty-making process in Canada. How do you believe the views of a treaty were different between Indigenous peoples and government officials?

Indigenous communities believed they were agreeing to share their land in exchange for things such as annual money, schools and teachers, farm tools, ammunition, and land reserved just for their use and the right to hunt and fish. The government, however, saw the treaties as huge surrenders of land that brought the First Nations under government control. Some promises have still been unfulfilled. Treaties one through seven were signed between 1871 and 1877, and treaties eight through eleven were signed between 1899 and 1921.

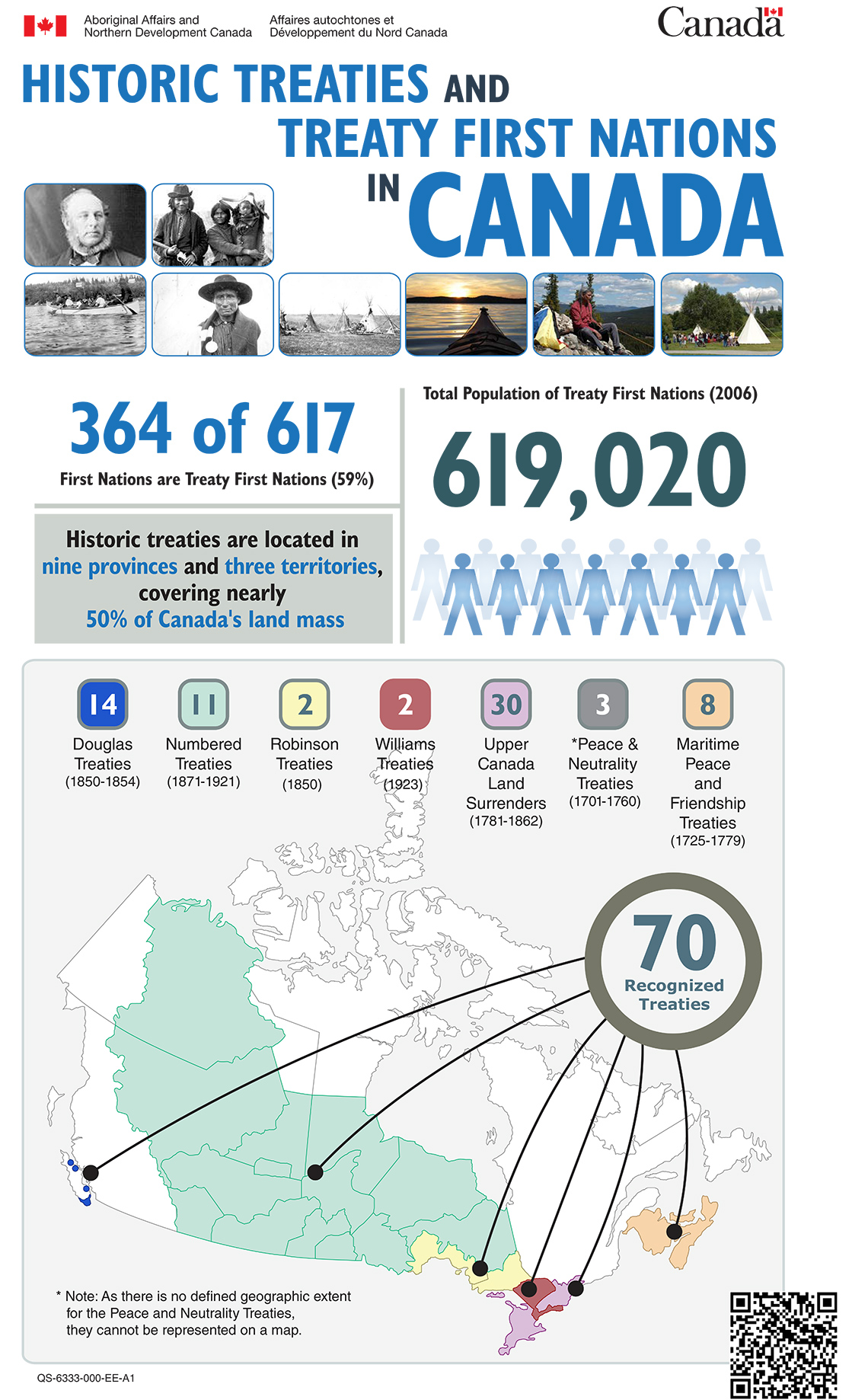

Use the Historic Treaties and Treaty First Nations in Canada Infographic to learn more about the history of treaties in Canada. Once you have finished exploring the infographic, answer the reflection question.

As we work towards Truth and Reconciliation, information about lands and territories is constantly being updated. This map was accessed through the permission terms of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development in July 2021.

Description

Description

The title of this infographic is, “Historic Treaties and Treaty First Nations in Canada.” This infographic includes facts with numbers about the different treaties in Canada.

Some of the facts that are stated in this infographic are:

- 364 of 617 First Nations are Treaty First Nations (59%).

- Historic treaties are located in nine provinces and three territories, covering nearly 50% of Canada’s land mass.

- Total Population of Treaty First Nations (2006): 619,020.

At the bottom of the infographic, there is a map of Canada showing the different locations of the different treaties.

There is a circle in this infographic that has text that reads, “70 recognized treaties.” This circle branches off to each treaty area on the map. The following are the treaties that were mentioned:

- Douglas Treaties (1850-1854) are located in British Columbia.

- Numbered Treaties (1871-1921) are across Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario.

- Robinson Treaties (1850), Williams Treaties (1923), and Upper Canada Land Surrenders (1781-1862) are located mostly in Ontario.

- The maritime Peace and Friendship Treaties (1725-1779) were located across Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Lastly, Peace and Neutrality Treaties (1701-1760) were not represented on the map.

At the bottom of the map, there is a note that reads, “As there is no defined geographic extend for the Peace and Neutrality Treaties, they cannot be represented on a map.”

Press ‘Reflection’ to access an inquiry that may help you think further.

Press ‘Reveal Answer’ to access ideas behind the names or titles of the different treaties.

There is a lot of information found on this infographic. What are three questions that this information answers?

Métis exclusion from the treaties

Métis peoples are of mixed First Nations and European ancestry. The Métis history and culture draws on diverse ancestral origins, such as Scottish, Irish, French, Ojibwe, and Cree. Métis communities emerged as a result of North American fur trade, during which First Nations peoples and European traders forged close economic ties and personal relationships. Over time, many of the children born of these relationships developed a distinct sense of identity and culture. Within their communities, they shared customs, practices, and a way of life that were distinct from those of their First Nations and European ancestors. Métis communities formed along strategic water and trade routes well before colonizers assumed political and legal control of these areas. Many of their communities persevered and continue to celebrate their distinct identities and histories today, practising their unique cultural traditions and way of life.

In some of the Numbered Treaties, the Métis had considerable activity during treaty negotiations as their own distinct nations advocating alongside their First Nations allies. However, in many cases, they were completely excluded from the treaty itself, because they were not classified as “Indians” under the Indian Act.

Research the Métis and Rainy River and Treaty 3. From your research, use the historical significance checklist from earlier in this learning activity to assess the historical significance and the impact this event had on Métis sovereignty. Begin your research using Canadian encyclopedias, virtual museums, and the Métis Nations of Ontario website.

Press ‘Important Note’ to access a piece of information that is important to know.

Land grants to the Moravian church in Nunatsiavut (Labrador)

The Inuit in Nunatsiavut (Labrador) did have extensive contact and experienced colonization at a much faster rate than the Inuit in Arctic communities. During Confederation, the Inuit of Nunatsiavut experienced colonization that included changes to their lifestyles and policies that were imposed upon them.

As you read, think about how policy impacted Indigenous sovereignty at this time and consult your Historical Significance Checklist.

Inuit from Nunatsiavut are called Nunatsiavummiut. The Nunatsiavummiut lived a nomadic lifestyle following traditional hunting patterns until the 1770s, when missionaries, particularly Moravian missionaries, came and developed permanent settlements in Labrador.

Press ‘Definition’ to access the meaning and definition of the word “missionaries.”

As trade and exposure increased between the Inuit and the Europeans over the next two centuries, so did efforts to assimilate the Inuit.

The British Government supported the efforts of the Moravian Church and provided them with large land grants, which would become the communities of Nain, Okak, Hopedale and Hebron. These lands had been travelled on and used by the Inuit of Nunatsiavut for thousands of years. The Church was made responsible for providing services to the Inuit including education. In 1926, all operations were transferred from the Moravian Church to the Hudson’s Bay Company.

In 1949, when Newfoundland officially became a part of Canada, the provincial government began providing services to the Inuit communities. In 1950, the government then made a decision to close many Inuit communities and move them further south. This caused more disruption to the Inuit way of life.

Explore the following map of Nunatsiavut communities in Newfoundland and Labrador.

As we work towards Truth and Reconciliation, information about lands and territories is constantly being updated. This map was created using information available as of July 2021 from The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Description

Description

Using the following Historical Significance Checklist, assess the historical significance and the impact this event had on Inuit sovereignty.

Historical significance checklist

Now that you have read three historical examples of challenges to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit sovereignty respectively, you will communicate your findings. A big part of historical significance is being able to discuss why this event is important and identify why people today should know about it.

In a written paragraph or an audio recording, answer the following question: Why are these three events significant to understanding First Nations, Métis, and Inuit sovereignty?

Task 2: Perseverance and resistance

Indigenous peoples did not just accept these policies that infringed upon their rights and sovereignty. Instead, they lobbied, resisted, and persevered by practising their unique cultural traditions and advocating for recognition and equality, despite ongoing oppression from colonial governments. The government’s plan to eradicate them through assimilation did not work because of the continued resistance of Indigenous individuals, groups, communities, and organizations.

Description

Description

This is an image showing the timeline of the Indian Act.

1876: The Indian Act is created and Indigenous communities self-government is extinguished.

1880: Policy forces Indigenous communities to get permits to sell goods and buy groceries and clothes.

1884: All Indigenous children are forced to go to Residential Schools where they are not allowed to speak their own language or practice their culture.

1885: Indigenous peoples are banned from practicing their own spiritual ceremonies and now require a pass to leave the reserve.

1914: Indigenous peoples must get permission before wearing traditional clothes at any public event, and dancing is outlawed off the reserve.

1918: The government gives itself the power to lease out Indigenous land to non-indigenous persons for farming.

1927: Indigenous peoples are banned from hiring lawyers regarding land claims without government approval.

1951: Bans on ceremonies, dances and land claims are removed. Women can now vote in band Council elections. Indigenous peoples who receive a post-secondary degree lose status.

1961: Indigenous peoples are finally allowed to vote in elections (the right to vote on land that was stolen from them).

1973: The Supreme Court rules that indigenous peoples do have rights to land.

2015: The Supreme Court rules that several provisions in the Indian Act violate section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

2021: The Indian Act is still being debated and amended.

The Indian Act not only defines who is a status “Indian,” but it also determines who can pass down their status to the next generation. In this way, the Indian Act aimed to assimilate generations of First Nations peoples by not recognizing them as “Indian” under the Indian Act. The federal government decides who can and who cannot gain status. Though the Indian Act does not specifically state blood quantum, or the percentage of First Nations ancestry a person has, it is how status is determined (unless applying for status for adopted children).

The Indian Act aimed to reduce the strength of matrilineal systems.

Press the ‘Definition’ button to access a definition of matrilineal systems and their place in Indigenous communities.

First Nations women fought tirelessly to have their rights restored and for equality under the Indian Act. There were three specific court cases that helped advance the rights of First Nations women and amend the Indian Act in 1985.

Timelines, like the one you have just reviewed, are helpful tools to illustrate the historical significance of different events.

Research the impacts of Jeannette Corbiere Lavell, Yvonne Bedard and Sandra Lovelace on amendments to the Indian Act. You will want to use your Historical Significance Checklist to ensure you’ve included all of the important information on your timeline.

The Métis fought for their lands and rights to be recognized in the Fort Frances area in the 1870s. They exerted much effort so that they were included in Treaty 3. After being recognized as a nation with “Half-Breed Adhesion to Treaty No. 3” in 1875, the passage of the Indian Act in 1876 led federal officials to deny the Métis of Rainy Lake and River recognition as a distinct Métis group while also denying having to uphold the Crown’s commitments made to them.

The Métis of Rainy Lake and River were provided only two options at the time. They could identify as “Indians” under the Indian Act or remain Métis and receive no benefits from Treaty 3 even though this violated the terms of the Treaty itself. Some members did decide to become “Indians,” but the majority did not. They did not curb to government pressures and were steadfast in belief that they were a distinct community and the Métis, a distinct nation. Since 1875 to present, they continue to hold the government accountable to their promises made under Treaty 3.

During the 1960s and into the 1970s, the Métis organized with Non-Status Indians, as both were left out of most of the government policy and discussions. Provincially, Métis gathered and organized to fight for their rights and recognition. And in 1971, the Native Council of Canada would come to represent the Métis and Non-Status Indians on a national level. Later, in 1983, the Métis National Council would emerge to represent the needs of the Métis nationally.

Métis people of Rainy Lake and River persevered through their fight for recognition and continued to exist as distinct people within Northwestern Ontario. Today, their community is recognized as a historic community and nation. They are recognized and are represented by the Métis Nation of Ontario.

During the 1960s and 1970s, many Indigenous peoples and organizations began lobbying for their rights. With the severe impacts European settlers had had on Inuit life, in 1973, the Labrador Inuit Association was created with the plan to promote Inuit culture, protect the health, well-being and rights of the Labrador Inuit communities and to assist in forming land claims. In 1977, a land claim was filed by this association to both the provincial government of Newfoundland and Labrador and the federal government. They reached an agreement in 2001 and the agreement became finalized in June of 2005. In addition to self-governance, the agreement provided the Labrador Inuit with:

- surface title to 16,000 km2 of land

- harvesting rights and shared rights to approximately 44,000 km2

- a percentage of the Voisey Bay project

Then came the official word on December 1st, 2005 that Nunatsiavut would have their own regional government, within the Newfoundland and Labrador government. Members of the Labrador Inuit Association became the government until their first election.

Today, the Inuit communities in Nunatsiavut continue to practise their traditional way of life of hunting, fishing, and gathering as well as governance over their home territories.

Source: Pedersen, 2006

Test Your Skills!

Check your understanding

Choose one of the examples of resistance that you have just explored and explain the specific actions that this group took to improve the lives of Indigenous communities. Explain why these actions are significant in Canadian history.

- Women’s Resistance to The Indian Act

- Métis Resistance of Treaty 3

- The Inuit of Nunatsiavut

Reflect

- What actions are being taken today by First Nations, Métis, and Inuit to recognise, preserve, and restore Indigenous nationhood both in Ontario and across Canada?

- How are these actions different from actions taken in previous eras?

- In what ways are present-day actions similar and/or different from actions taken by activists of the past?

Consolidation

Nation-to-nation relationships

A way of understanding Indigenous sovereignty is to think of Indigenous communities as independent nations that exist and operate within a larger nation (Canada). Simply think about Indigenous groups as “nations within a nation.”

But, despite the resilience and ongoing resistance demonstrated by Indigenous communities, Indigenous sovereignty has not been fully restored to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. It takes supporters and allies to help educate and advocate for Indigenous rights alongside Indigenous peoples.

How could you use your understanding from this learning activity to help you challenge misinformation about the history of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis sovereignty with the Canadian government?

Think of three ways that you can use this information to disrupt everyday conversations where you might hear someone say something uninformed about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit individuals, communities, rights, and sovereignty.

For example, many people might believe all Indigenous peoples are under the Indian Act or that Confederation benefited every person living in Canada.

Select three scenarios from the following list to educate others about.

- Explain to someone how Confederation and its policies thereafter aimed to undermine Indigenous land rights and sovereignty.

- Explain to someone how Canada legally defines terms for and classifications of Indigenous peoples.

- Explain to someone how Métis sovereignty was challenged in the treaty-making process.

- Explain to someone how Métis peoples are included in the Treaties.

- Explain to someone how federal legislation has affected the cultural identities of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit individuals and communities in Canada.

- Explain to someone how policies aimed to forcefully remove Indigenous peoples from their traditional territories.

- Explain to someone how the Indian Act aimed to reduce women’s power.

- Explain to someone the impacts of colonization on the Inuit well-being and their lands.

Reflection

As you read the following descriptions, select the one that best describes your current understanding of the learning in this activity. Press the corresponding button once you have made your choice.

I feel...

Now, expand on your ideas by recording your thoughts using a voice recorder, speech-to-text, or writing tool.

When you review your notes on this learning activity later, reflect on whether you would select a different description based on your further review of the material in this learning activity.