Minds On

While the content in this learning activity is aligned to the curriculum,

some content may be sensitive to individual learners. Consider reaching out to a trusted

adult to share your feelings and questions.

What are turning points?

Turning points are an important part of being able to identify, analyse, and assess different parts of history. Turning points can pinpoint if times are that of continuity (stability) or change.

Change is a process that varies in its patterns, meaning how rapidly or how deep the change is felt by society. Turning points are moments when the change shifts in direction or in pace.

Turning points exist everywhere, not just in the world or Canadian history, but in every single person’s life as well. Let’s think about your turning points.

- Think about any points in your life that you can identify as turning points. What are the times or moments you remember that altered the course of events in your life?

- Looking back, what are some of the distinct periods of your life? What makes them distinct? (e.g., an important event, a time of transition or change, etc.)

- Throughout these periods, what parts of your life stayed the same? (e.g., ideas, events etc.)? This helps you identify the continuity within times of change.

Student Success

Think-Pair-Share

Create a map of your life using a method of your choice. You may wish to design your map as a timeline in chronological order to help identify times of change. What eras or periods of time can you identify and label (e.g., childhood, early years, beginning of school, etc.)? Don’t forget to identify significant events, people, and dates on your life map. If possible, share your creation with a partner.

Note to teachers: See your teacher guide for collaboration tools, ideas and suggestions.

Press ‘Reflection’ to access guiding questions that might help you develop some thoughts.

- What are some of the ways you divided your life? How did you separate one period from another in your life?

- What events or people remained the same throughout your life? Which events or people changed?

- How and why did these changes occur?

- How are the events in your map related to family, school, and your community?

Action

Continuity and change

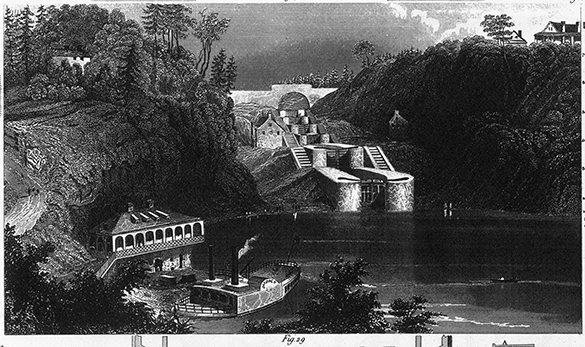

Rideau Canal, 20th Century

Rideau Canal, 21st Century

As you learned in the Minds On section, a turning point is a historical event which is significant or is a time of progress or change. Throughout this activity, as you learn about the residential school system, you will be identifying and assessing events, people, and concepts as times of continuity or change and whether or not an event should be considered a turning point.

As you explore the information throughout this learning activity, you can evaluate various important events, concepts, or individuals by using the Continuity and Change chart provided. Every time there is a “CHECKPOINT,” you should be pausing for reflection and adding new information to your graphic organizer.

There are some helpful guiding questions to aid in your evaluation of the degree of change (located in the final column of the chart). Questions are:

- Stability and Change: What stayed the same and what changed as a result of the event?

- Pace and Depth of Change: Was the impact of the change widespread and deep or was it narrow and shallow? What were the key turning points in the event? What is the pace and the direction of change caused by key turning points?

- Historical Significance: What examples of progress or decline resulted from the event? Describe the progress or decline in social, political, legal, economic, environmental, cultural, and/or technological terms.

For rating the degree of change, use this scale:

Rating scale:

4 = complete change

3 = moderate change

2 = minimal change

1 = continuity (no change)

|

Event, individual, concept |

Its significance in the past context |

Its significance today |

Rate the degree of change on a scale |

Is this a turning point? Why or why not? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rating (1-4) : (Blank) because…(Blank) |

||||

|

Rating (1-4) : (Blank) because…(Blank) |

||||

|

Rating (1-4) : (Blank) because…(Blank) |

||||

|

Rating (1-4) : (Blank) because…(Blank) |

||||

|

Rating (1-4) : (Blank) because…(Blank) |

Press the ‘Activity’ button to access Continuity and Change.

Task 1: The residential school system

The Indian Act and the residential school system

The start of assimilation through education began much earlier than the residential school system. From the 1600s to 1800s, church-run schools were in operation with the aim of assimilating Indigenous peoples into their religious beliefs and values.

Press ‘Assimilation’ to access its definition.

Through the British North America Act, the Canadian government implemented a system in which they took control over Indigenous peoples. With this shift, attitudes and treatment of Indigenous people began to change. The push to assimilate Indigenous peoples increased.

Press ‘The British North America Act’ to access what this document is.

Before the Indian Act was enacted in 1876, it was preceded by other legislation (later combined to form the Indian Act), such as:

- the Act to Encourage the Gradual Civilization of Indian Tribes in this Province, and to Amend the Laws Relating to Indians (also known as the Gradual Civilization Act) in 1857

- the Gradual Enfranchisement Act, in 1869

These documents revealed the government’s plan to have First Nations peoples rescind their status and become “civilized,” as defined by the government, and part of the Canadian population.

Under the Indian Act, the federal government mandated the education of First Nations’ children and entered into a partnership with the churches to provide First Nations children education with a focus primarily on assimilation. Inuit and Métis peoples were not included in the Indian Act but were enrolled in the schools, nonetheless.

Explore the following video “What is a Residential School?”. While you are exploring, think about how certain events, people, or ideas are significant and create change in society. Record your ideas using a method of your choice.

Timelines are useful tools to track major events over a broad period of time. Timelines can also make it easier to visualize the events that were historically significant in a particular time period.

You will now explore the interactive timeline "Felt Throughout Generations’: A Timeline of Residential Schools in Canada." After you have finished reviewing the timeline, respond to the questions that follow.

Press tvo today to access "'Felt Throughout Generations’: A Timeline of Residential Schools in Canada.".

Opens in a new tab- Which of the events from the residential schools timeline do you think are the most significant from your point of view? Select five important events to add to your Continuity and Change chart. You can continue to add to your chart as you deepen your knowledge and understanding throughout this learning activity.

- Consider how these policies might signal turning points in government policy as well as Indigenous life.

Residential school experiences

As you learned from the timeline, there were approximately 139 recognized residential schools in operation across Canada, which operated from the mid-1880s until 1996. One of the core purposes of these schools was to eliminate Indigenous culture and traditions. The schools wanted to make the Indigenous populations indistinguishable from others in mainstream society. The intention was to assimilate them into the dominant culture, thereby ensuring that there would no longer be a distinct Indigenous population in Canada. Assimilation, like colonization, is a violent act.

The residential school system aimed to specifically assimilate Indigenous children and did so through calculated and purposeful steps that ensured that Indigenous children would be far-removed from their rich cultures, traditions, and knowledge systems. The following is a list of some of the methods the federal government used to ensure assimilation:

- Children were removed from their homes and communities: Children were taken from their homes and communities and forced to attend schools that were sometimes hundreds of kilometers away from where they lived. It became illegal for Indigenous parents to keep their children at home if they were of schooling age. Some children were taken at even earlier ages, and some did not return to their communities until the age of 18, if at all. As a result, many lost connections to their home communities and did not grow up learning from their parents, grandparents, or community Elders. It was thought that children were easier to be taught these beliefs than adults, and that they would later pass on their newly-acquired culture to further generations, thereby ensuring the complete annihilation of Indigenous culture in Canada.

- The use of non-Indigenous languages: Children were given Christian names to replace their traditional names and were clothed in Western-style clothing. English or French had to be used in the school, and traditional languages were banned in classrooms and could not be spoken at school. In certain circumstances, severe punishments were inflicted on children who were caught practising an Indigenous tradition or speaking or writing in their traditional languages. Thus, when children did return home after years of schooling, they no longer spoke the languages of their parents or grandparents.

- Substandard education and abuse: Most students who attended these schools did not receive the education that the government and church had intended. Many did not learn or master any school-related skills; rather, they were forced to do manual labour. Many were taught by inexperienced staff and unlicensed educators, and many were sexually, physically, and/or emotionally abused.

Though not all the experiences of children who attended residential schools were negative, many children lived in substandard conditions in the schools and often endured years of abuse. These children often wished they had been raised by their families in their communities and had the opportunity to also learn from family life.

The experiences of survivors of residential schools varied due to many factors, including the following:

- the school

- the age of the child who attended

- the religious organization that ran the school

- the school’s budget

- the staff who worked at the school

- the proximity of the school to the student’s home

- whether it was a day or residential school

Though the lives of each individual student differed, many survivors have recalled similar daily routines and schedules, with time allotted for chores, mass (church service), and academic learning.

The following is a description of daily life at Kamloops Indian Residential School (KIRS) based on interviews from survivors.

Press 'A Typical Day at Residential School' to access how students at the Kamloops Indian Residential School would spend their day at school.

A Typical Day at Residential School

Carefully examine “A Typical Day at Residential School” for a student at KIRS. As you read, make note of anything you notice about the schedule.

A TYPICAL DAY AT RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL

- 5:30 am: Boys are doing the morning chores, milking the cows and feeding the animals

- 6:00 am: Everyone else got up

- Went to Chapel for morning mass

- Breakfast:

- Sticky porridge cooked by students the night before

- A piece of bread with butter

- A glass of milk

- Morning cleaning duties

- Classes:

- The first hour was religious studies

- The next two hours were academic studies (math, reading, writing)

- Work Time/Chores

- Girls learned to sew, laundry, cook, and clean

- Boys learned to farm, grow a garden, and chop wood

- Some boys learned basic carpentry and shoe repair

- Cleaning groups cleaned their designated part of the school

- Study hour

- Supper

- Clean-up

- Recreation time

- Prayers

- Bedtime

Source: Haig-Brown, 2013

The half-day system

The schedule you just reviewed reflects what is called a half-day system. The half-day system was designed so that students spent half the day in class and the rest of the day maintaining the school through domestic chores and trades.

Church-run residential schools mainly operated on a half-day system until 1951, when it was abandoned as a result of changes made to the Indian Act. However, this did not mean that all schools followed the amendments, and some continued to run this system long after 1951.

While no two residential schools were exactly the same, it’s important to understand the following elements of the half-day system:

- The curriculum was divided into moral (religious), academic, and industrial training (chores or skilled trades). Student tasks were divided according to gender. The tasks of girls consisted of domestic work and included cooking, cleaning, and sewing. Boys focused on manual labour, farming, learning metal or blacksmith work, and doing general physical labour in and around the school.

- Half-day systems were not always adhered to, and it happened that students were sometimes forced to work all day so the schools didn’t have to pay for labour and could keep costs at a minimum, as federal funding for the schools was declining.

- In comparison with non-Indigenous students, Indigenous students had, on average, five hours less of instructional time per day. As a result, most residential school students in the half-day system did not go beyond a primary level of education. In some schools, an age-grade system was implemented that kept students enrolled until they were 16 years of age and in Grade 8. Thus, each student was held back two grades before being allowed to graduate and enter secondary school. As a result, these systems adversely affected many of the students’ self-esteem as well as their ability to learn.

Press ‘Checkpoint’ to access guidelines that will allow you to add to the Continuity and Change chart.

Listening to survivors

For many years, survivors of the residential school system were not believed. Over 150,000 Indigenous children attended residential schools. Each survivor’s experience was different. Some survivors recall an enjoyable school experience, but the majority do not. Whatever way a survivor describes their experience is valid, as it is a personal testimony that reflects how they felt about their time at the school.

You will listen to and research First Nations, Métis, and Inuit survivor experiences in residential schools. Using your Continuity and Change chart, you will analyse the impacts that the residential school system had on Indigenous individuals, families, and communities and its significance to them today. As you listen and learn, add your learning to your Continuity and Change chart.

It is important to note that not every Inuk, First Nation, or Métis individual attended a residential school. Enrolment was based on the community in which they lived, the agents in charge of students attending, when the schools in their area opened, as well as additional reasons specific to each situation.

Press the different experiences to understand the experiences of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit individuals in residential schools.

Explore the following video in which the late Arthur Manuel discusses his experience during the 1960s as a student at a series of residential schools in British Columbia, including Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Métis survivors have had a difficult time getting their stories and experiences recognized and included in the documentation of residential schools. Métis students often went unrecorded in residential schools or were lumped into the same category as First Nations children in school records. As a result, some Métis residential school survivors have given themselves the label “The Forgotten.”

Day schools have also often been excluded as part of residential school history. Day schools were for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children. They were sent during the day, but in the evenings lived with their parents and remained in their communities. The goal of these schools was also assimilation. Like residential schools, many survivors of day schools recount different types of abuse such as physical, verbal, and sexual abuse.

Likewise, many Canadians also do not know or know enough about Inuit experiences and the history of colonization and education in the North.

Task 2: Impacts of the residential school system

Although residential schools were in operation for over 150 years, their impact and legacy continue to be felt long after the schools’ actual closure. As you learned in the videos, the trauma experienced in residential schools did not confine itself to one generation. Instead it spanned across the next or multiple generations thereafter. When trauma affects more than one generation, it is called intergenerational trauma. Residential schools were the result of violent and destructive policies that aimed to divide communities, land, and family. Intergenerational trauma affects survivors who went to a residential school, as well as those who did not attend but whose family members may have. Intergenerational trauma is not only experienced by people who have had some relationship to residential schools in their family. Rather, there are many ways through which Indigenous people may experience intergenerational trauma that stems from colonization and its many forms. It is important to remember that intergenerational trauma, and trauma in general, affects each person differently.

Press ‘Checkpoint’ to access guidelines that will allow you to add to the Continuity and Change chart.

From your learning, what conclusions can you draw about how residential schools affected and continued to affect the Indigenous individuals, families, and communities? Add the Impacts of Residential Schools to your Continuity and Change chart.

Task 3: Survivors fight for truth and justice

Orange Shirt Day (which is also known as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation) occurs annually on September 30. This day acknowledges and promotes awareness of the residential school system and its lasting impacts on Indigenous communities across Canada.

Despite the efforts of the church and federal government, residential schools did not eradicate Indigenous culture. Assimilation and cultural genocide were at the core of the intentions of the residential school system, but the system was unsuccessful. Indigenous peoples fought to regain their culture and the teachings and ceremonies that had been banned by the Indian Act, government, the church, and the residential school system. Indigenous peoples have experienced loss, grief, and trauma through the direct and intergenerational impacts of this school system, and they have fought hard against the injustices they have suffered.

As a way to seek amends, including funds to create healing and wellness resources for survivors, in the 1980s, residential school survivors began launching lawsuits against the government and the churches involved. Finally, in 1998, almost two decades later, the federal government acknowledged the experiences of those in residential schools through the Statement of Reconciliation.

Press ‘What is Reconciliation?’ to access its meaning.

Explore the following video “What is Reconciliation?” to further your understanding.

Inquiry

For this activity, it will be helpful to understand the Inquiry Process.

Press ‘Inquiry’ to access its multi-step process.

An inquiry is a multi-step process used to:

- formulate questions

- gather, organize data

- analyse information

- evaluate and draw conclusions

- communicate results

Although the stages are not always done in the same order, this graphic from the Ontario Ministry of Education provides a summary of these steps. Examine the diagram to see how the steps relate.

A graphic representing the inquiry process. There are five stages to the inquiry process, but they are not always done in the same order. One stage is Interpret and Analyse. At this stage we analyse the data, evidence, and information, using different types of graphic organizers as appropriate. Another stage is Gather and Organize. At this stage we collect and organize relevant data, evidence, and/or information from primary and secondary sources and/or field studies. Another stage is Formulate Questions. At this stage, we formulate questions related to the applicable overall expectation in order to identify the focus of their inquiry. Another stage is Evaluate and Draw Conclusions. At this stage we synthesize data, evidence, and/or information, and make informed, critical judgements based on that data, evidence, and/or information. Another stage is Communicate. At this stage, we communicate judgements, decisions, conclusions, predictions, and/or plans of action clearly and logically.

Let's use the inquiry process to think about Indigenous policies in Canada. How can the policies and actions that we have explored be considered turning points in government and Indigenous actions? You will be focusing on the following policies and actions for this task:

- The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA)

- The Apology (from the Canadian government)

- The Truth and Reconciliation of Canada (including Calls to Action and the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

- Indian Day School Settlement

As you are investigating these policies and actions, consider the following questions:

- What does this policy or action acknowledge? (Think about what they are bringing awareness and attention to)

- Who was involved in this policy or action? (Consider both who created or made it and whom it was directed towards)

- Why is this policy or action important? (Think about what the point of this is, what is the goal?)

- How does this policy or action bring awareness to the trauma Indigenous communities have suffered and how is it trying to make amends for what had happened in the past?

Begin your research by exploring the Truth and Reconciliation of Canada government website, virtual Canadian encyclopedias, and Indigenous community websites.

When you are finished, explore the provided information in the following "Answer key" section to ensure historical accuracy. After you have explored this information, add each of these events to your Continuity and Change chart.

Answer key

Press each tab to access thoughts and ideas that you might have thought of while thinking about the responses to the questions.

From the work and discussions of the survivors and their representatives, National Indigenous Organizations, the federal government, and the churches who played a role in the residential schools’ system, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) was implemented in September 2007.

The IRSSA not only acknowledged the pain and abuse inflicted upon the survivors of the residential school system, but also recognized the need to assist and support survivors with the healing process.

With well over one billion dollars in approved payments, the IRSSA remains the biggest class action settlement in Canadian history. The agreement applies to an estimated 80,000 to 90,000 residential school survivors but does not apply to those who attended day school or boarding school.

As you have learned, survivors of residential schools were silenced, and their stories were not heard of or talked about publicly for decades and sometimes centuries. It has only been in recent years that steps have been taken to acknowledge these experiences.

A step towards acknowledging what happened in residential schools came from the federal government on June 11, 2008, when Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized to survivors for what happened to them in residential schools across the country. Through years of hard work and resilience, Indigenous peoples’ experiences as well as the intergenerational impacts of residential schools were recognized.

The battle for justice wasn’t over when the IRSSA was created. Rather, it had, in many ways, just begun, with all the components of the IRSSA taking years to implement and support. One well-known component of the IRSSA was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

A Truth and Reconciliation Commission is a way to investigate and report on a government or formal governing body’s past wrongs in order to rectify the relationship between those affected and the governing body. In addition to all the elements that are present in a truth commission, the reconciliation aspect of this kind of commission includes a focus on the present and the future.

A truth and reconciliation commission aims to reconcile the present and future through the use of restorative justice, which is a system of criminal justice that focuses on the rehabilitation of offenders (in this case, the Government of Canada) through reconciliation with victims and affected communities.

Restorative methods can include, but are not restricted to:

- formal apologies

- reparations to the victims

- commemorations including monuments that acknowledge past injustices

- peace agreements (which can be used as a way to bring together divided elements of the country, especially when those who committed the crimes cannot be punished due to impunity or time elapsed)

The TRC was created to help ensure survivors were given an opportunity to share with the rest of Canada what happened to them in residential schools. A common misconception is that the federal government paid for the TRC. It was actually the survivors who allocated a portion of their settlement money to ensure that a TRC took place.

Although the TRC had challenges, the commission overcame its obstacles and eventually completed its mandate to create The Calls to Action to lead Canada forward towards Reconciliation.

Following a closing ceremony in Ottawa, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) completed its mandate with the publication of its final report, Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. This report documents the legacy and history of residential schools through testimonies from more than 300 communities taken from over six years of interviews. Ahead of the 536-page report, the TRC published a 20-page document, “The Truth and Reconciliation of Canada: Calls to Action,” which includes 94 recommendations meant “to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation.”

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) was established as part of the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg and is where all the documents, statements, and artifacts collected by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission are housed. The NCTR houses and presents audio testimonies and print archives that have been digitized so people across the country and around the world can gain access to them.

In 2009, Garry McLean began legal action seeking justice for day school survivors. In August 2019, the Federal Court approved a nation-wide class settlement to compensate survivors of day schools.

Student Success

Extend your learning

You can further extend your learning by researching the progress made towards fulfilling the Calls to Action. How many Calls have been fulfilled to date?

Consolidation

What can Canadians do to support truth and reconciliation?

It is important to remember that Indigenous peoples continue to work to raise awareness and be active citizens to create political change in their own communities as well as on a national scale.

Explore part of the video “Canada’s Residential School Legacy” to learn more about what Canadians and the government of Canada can do to support Truth and Reconciliation.

After you have finished the video, complete the following tasks as part of what you can do to support survivors and Truth and Reconciliation at an individual level.

Task 1: Express gratitude

As you have learned, survivors of residential and day schools were silenced, and their stories were not heard or talked about publicly for decades and sometimes not even during their lifetimes. It has only been in recent years that steps have been taken to acknowledge these experiences.

Think of a way that you could express your gratitude for the survivors who shared their stories. Select one of the following ways to express your gratitude:

- write a poem or song

- create a poster in print or digitally

- write a newspaper article

- create of piece of art, accompanied by a written explanation

- complete a short essay in print or digitally

- create a blog post or podcast episode

Task 2: Educate

One of the main goals of Truth and Reconciliation was to educate and elevate the voices of survivors and their experiences. Review your Change and Continuity chart.

Next, select three of the events that you designated as turning points that you feel you could educate others about, including the history of this event, person, or concept and its significance today.

Create a set of social media posts that could educate others in an accessible way. Include hashtags and images to make your posts engaging for an audience. Use the following checklist to guide each post.

Task 3: Reflect

Student Success

Think-Pair-Share

Respond to the following questions using a method of your choice. If possible, discuss these questions with a partner and compare your views and perspectives

- In your opinion, which of these events were the most significant turning points? Which of these events do you think stimulated the most change?

- How do survivor testimonies remind you about the importance of listening to Indigenous peoples? How might this help you throughout your life?

- Why is it important that the Calls to Action be fulfilled? What are some actions you could take to continue supporting Truth and Reconciliation throughout your life?

Note to teachers: See your teacher guide for collaboration tools, ideas and suggestions.

Reflection

As you read the following descriptions, select the one that best describes your current understanding of the learning in this activity. Press the corresponding button once you have made your choice.

I feel...

Now, expand on your ideas by recording your thoughts using a voice recorder, speech-to-text, or writing tool.

When you review your notes on this learning activity later, reflect on whether you would select a different description based on your further review of the material in this learning activity.